Build Apartments Above Your Shopping Centers

One weird trick to meet your city’s housing requirement WITHOUT upzoning single family neighborhoods

I live in Long Beach, California, and we have a housing shortage. Like every other coastal city in the State, there simply haven’t been enough new homes built over the last forty years to keep up with population growth, and the result is skyrocketing housing prices, inequality, and homelessness. The answer is obviously more housing units, and the state’s Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) set a target for each locality to meet over the next eight years. Long Beach is required to build over 26,000 new units by 2028 but the city’s housing element only identified sites for 12,653 potential homes. Even assuming all of those sites are legitimate that still leaves us some 14,000 units short of the requirement set down by the state, and the city, “is committed to amending the zoning code within three years,” to reach the target number.

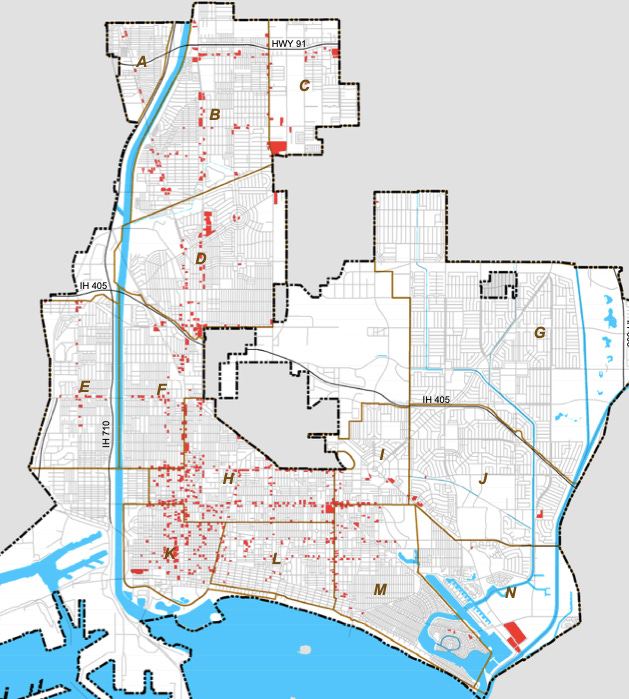

The other issue with the city’s plan is where to build all the new units; right now, most of them are expected on the West and North sides, clustered downtown and leaving the East side, and its wealthy single-family neighborhoods, largely untouched. That means the majority of the City’s planned units fall within formerly redlined districts and the Whiter side of Long Beach will build close to zero. Low-income neighborhoods need new units too, and mixed-income buildings can provide affordability without stigmatizing the project as, well, a Project. But the plan’s current concentration of units would exacerbate segregation and cause gentrification in the low-income neighborhoods inundated with new market-rate rents; affordability requirements can only do so much when low resource areas see intense development and adjacent wealthy neighborhoods stay exclusive.

But older, wealthier, home-owning Eastsiders are overrepresented at planning meetings and public hearings because, unlike poor younger folks, they didn’t have jobs, kids, and other commitments occupying their time on a random Monday night three years ago when these decisions were made. That’s the biggest problem with local control of housing production; the loudest voices in a town hall meeting are unlikely to represent the larger community’s best interests. This dynamic is why state legislators passed SB9 this session to override local restrictions in single family neighborhoods, legalize lot splits, and allow duplexes by right on those lots. But, while lot splits and duplexes will help build the missing middle, they are long-term answers to a short-term problem; we need lots of apartments right now.

That’s where things get sticky; if you saw how mad wealthy cities are about SB 9 just imagine their reaction to new apartment buildings in their backyard! While I don’t personally give a fuck what those wealthy homeowners want, I know the elected officials in my city and others can’t piss them off and expect to win another election. Rich angry old people are a powerful political force and their hallowed property values, likely the source of their wealth, is entirely off-limits. And just in general, they’ll fight any potential change to their built environment because humans are creatures of habit and change is scary, especially at that age. I don’t like it but those are the unfortunate truths of local politics; if you want to change anything, you’re always fighting against the grain.

Which (finally) brings me to my point: I know how to build all the housing Long Beach (or your city) needs, and then some, without up-zoning the precious single-family neighborhoods on the East side—but also without clustering all the new units in low-income areas. Every suburb in the state is sitting on a golden goose of housing production and they don’t even realize it: just build apartments above the grocery stores and strip malls. That’s it! Every big-box all-in-one store should have hundreds of units stacked on top; All our one- or two-story roadside retail centers should have at least three stories of apartments above the shops; every mall should be a complete community styled after a Barcelona superblock.

There are millions of square feet of under-utilized space just hanging out above your neighborhood Food-4-Less or Wal-Mart because, in most cities here in California, it’s against the law to build apartments on top of commercial space. All we need to change that is one city council meeting and a dream. More importantly, this is the way to build more housing without a) replacing cheaper units in low-income areas, driving displacement, or b) scaring politically-active homeowners with *gasp* apartments next door.

I looked at several examples here on the East side of Long Beach and found enough space to build all 26,000 units required by the RHNA without redeveloping a single existing residential structure or losing any retail space. Los Altos Market Center, for example, occupies 1.7 million square feet half a mile from Cal State Long Beach; Los Altos Gateway across the freeway is another 1.7 million, bringing the total to 3.4 million square feet. The average two-bedroom apartment in Long Beach is about 990sqft so, rounding up to 1000, those two shopping centers alone have space for close to 3000 units—per floor; including hallways and common areas, three or four stories built on top could be close to a third of the city’s required units.

The traffic circle area is another perfect example; over 3 million square feet in the heart of the city occupied by one-story retail and their expanse of parking lots. Four stories of apartments on top of all that space would create 10,000 or more units and leave the surrounding neighborhood untouched. These are high-end estimates of course, but even a fraction of this number would give businesses more customers and potential employees living on-site, including students at CSULB and workers at the nearby Long Beach Medical Center. Not to mention, the circle itself would become a community and a neighborhood, not just a pit-stop on PCH.

The Spring & Palo Verde mini mall down the street from Millikan High School is 1.4 million square feet, potentially 5,000+ units. Second Street in Belmont Shore is fifteen-blocks of bars, restaurants, and retail—all of them one-story buildings ripe for mixed-use redevelopment. Roughly 600,000 square feet total, the focal point of the East side could build 1800 new housing units with just three stories of apartments built above the strip. Do that for every single-use commercial zone in the city and you just found room for tens of thousands of new units, all of them medium-density urban infill, all of them walkable, community-centered neighborhoods.

Now, before you say, “bUt wHaT aBoUt pArKiNg??” I’d like to remind you all these retail centers have way too much parking already. Zooming out a bit, there are more than 100 square miles of parking in Los Angeles County, and that’s just the surface lots; add in street and garage parking and 14% of LA County’s land is devoted to parking, most of which is empty at any given point. But what I’m proposing wouldn’t get rid of those lots at all; in fact, it might increase total parking in the area by building a few garages instead of just surface lots.

Furthermore, I don’t care about parking. Every parking spot a housing developer builds adds thousands to the cost, a price that’s passed on to you as a renter or buyer. Every parking space built means fewer units built, more traffic on the road, and less money invested in people-oriented mobility—like walkability and public transit. Instead of asking for more parking in these new developments, we just need to build transit to serve those and other communities sorely in need. Build a few dedicated bus lanes or even a train or two, and they’re all transit-oriented developments. The fact that we’re NOT doing this already simply blows my mind.

The mandated separation of commercial and residential zones has arguably done more to entrench, and perpetuate, car-dependence and housing inequality than any restrictive covenant or redlining map. Those single-family home neighborhoods wouldn’t be so bad if we allowed mixed-use retail nearby and built several stories of apartments on top of their grocery stores, providing affordable housing for low-wage employees. Not to mention, this type of dense, walkable, retail-serving development is exactly what our dying main streets need and the type of neighborhood shown to foster community and strengthen social cohesion. Given the opportunity, I’d even go as far as to mandate every commercial zone in the state be changed to mixed-use and strongly encourage the corporations owning that land to re-develop for residential on top of the retail. Instead of desperately clinging to the old way of life it’s time to embrace the new—well, actually even older—peak urban form.